The Pagan Critic Who Knew Something: Porphyry

Neoplatonist philosopher Porphyry (234-ca. 305 AD) was a strong opponent of Christianity. His treatise, "Against the Christians", contained harsh criticism against the early church.

Christianity has always had critics and it always will. One notable opponent of early Christianity was Celsus. Around 178 AD, Celsus wrote this about the Christians: “Like all quacks they gather a crowd of slaves, children, women, and idlers. I speak bitterly about this”.1

The church of Christ has withstood all of these attacks – and it always will. The following list is from Chart 15 in the “The Arguments of the Apologists” in Robert C. Walton’s Chronological and Background Charts of Church History (2005). It offers a helpful summary of the points offered by early critics of Christianity:

Summary of pagan criticism:

– The doctrine of the resurrection is absurd

– There are contradictions in the Scriptures

– Atheism is widely held amongst Christians

– Christianity is the worship of a criminal

– Christianity is a new novelty

– Christianity evidences a lack of patriotism

– Christians practice incest

– Christians practice cannibalism

– Christianity leads to the destruction of a society

From the above summary, we get a sense of why the Apostle Paul said what he said in 1 Corinthians 1:18, “For the word of the cross is folly to those who are perishing, but to us who are being saved it is the power of God.”

With this in mind, what “resources” did early Christians have to offer potential converts, besides the promise of extreme ridicule and possible persecution? In the physical, the answer is nothing. But John 16:33 and Hebrews 11:35–40 provide the answer. This dispels the notion that people became Christians to make their lives “easier”.

One strident critic of early Christianity was a man named Porphyry. Theologian Louis Berkhof in his The History of Christian Doctrines, classed him with the likes of other critics: “Lucian, Porphyry, and Celsus, men of a philosophical bent of mind, who hurled their invectives against the Christian religion.”

Church historian Philip Schaff gave credit to Porphyry in his History of the Christian Church: “Porphyry attacked especially the sacred books of the Christians, with more knowledge than Celsus.” Who was this man who attacked the early Christians with such vigor, and what did he write? Let’s talk about it.

Porphyry

Porphyry (232-305 AD) was a student of Plotinus (205-270 AD) and a Neoplatonic philosopher.2 R.K. Harrison described him as one “who inveighed vigorously against Christian belief in a fifteen-volume work which has not survived.”3

Except for fragments, Porphyry ’s Against the Christians Κατὰ Χριστιανῶν is lost. These scraps include discussions regarding the date of Moses and critiques of the book of Daniel. From later writings which mention Porphyry, it is likely he mocked Jonah and Hosea and questioned both the consistency of the four Gospels and the wisdom of the apostles.4

His main point regarding Daniel was that Christians were mistaken in their reading of Daniel as prophecy. Celsus held that Daniel should be read as contemporaneous history with the author. This position — that Daniel was a Maccabean forgery — is essentially the position held by many modern Old Testament critical scholars. 5

Part of his polemic is preserved in Jerome’s commentary on Daniel. Porphyry reasoned “from the a priori assumption that there could be no predictive element in prophecy.” 6

According to Jerome, Porphyry “claims that the person who composed the book under the name of Daniel made it all up in order to revive the hopes of his countrymen. Not that he was able to foreknow all of future history, but rather he records events that had already taken place.”7

Porphyry attacked Daniel because it was a prophetic proof book for Jesus as Messiah, as seen in the writings of a number of Christian apologists such as Justin Martyr and Hippolytus of Rome.

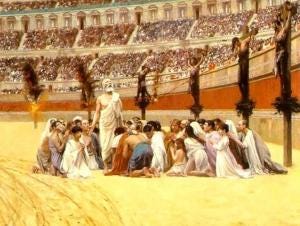

Porphyry’s work included stock criticism, such as Christianity is “an unreasoning faith”.8 He also pined on what he saw as the general absurdity of the Christian doctrine of the resurrection. He also (likely) complained that Christians were bad neighbors who “do not go to our shows … take no part in our processions … are not present at our public banquets [and] shrink in horror from our sacred games".9

Porphyry, in a critique raised by Celsus as well, attacks the Christian view of divine revelation taking place in history: “If Christ says he is the way, the grace, and the truth, and claims that only in himself can believing souls find a way to God, what did the people who lived in the many centuries before Christ do … why did he who is called the Savior hide himself for so many ages?”10

Porphyry took issue with the whole idea of God being crucified, if his passing on an oracle by Apollo is any indication. Here we see the phrase “vain delusions” used to describe those who lament “in song a god who died in delusions, who was condemned by judges whose verdict was just…”.11

Porphyry wrote another significant work titled Philosophy from the Oracles. Historian Robert Wilken, who dubs Porphyry “the most learned critic of all”, summarizes the strength of this work when he says that it “was a philosophical treatise in defense of the traditional religion” and “it may have well had a subsidiary purpose in providing a rationale for the persecution of Christians”. How? Because Christians “in forming a new religion devoted to the worship of Jesus, not only turned men away from the worship of the one supreme God … but also undercut traditional piety”.12

This means Porphyry’s work could function as the theory behind the practice of persecuting Christians.

CRITICISM & PERSECUTION IN CONTEXT

Towards the end of John 15, as part of the Farewell Discourse (John 15:18–16:4) , Jesus told his disciples that they will be hated by the world for his names’ sake. Gentiles disliked Jews for some of the same reasons for why they disliked Christians: both groups were exclusive. In a multi-cultural world filled with gods and various philosophies, Christians were called ‘The Way’. But the idea of Jesus being The Way to the Father (John 14:6) is offensive to the unregenerate mind.

The exclusive claims of Jesus and his followers were/are viewed as simplistic, backwards, ignorant, naïve, arrogant, bigoted, and even hateful. The Christians preached there was only one name under heaven by which men could be saved (Acts 4:12). They told the Gentile pagans they were wrong and challenged them to recognize Christ alone as God and Savior in places like Acts 17.

Christians would not burn a pinch of incense and swear by the genius of the Caesar. They were not willing to simply add their neighbor’s deities to a pantheon, as a sort of a cultural common courtesy. The early church would not go this direction, despite the many cultural obstacles in front of them; least of which was the fact they followed a convicted criminal.13

Simultaneously, the leaders of Judaism steadfastly denied – and even attacked them. In John 16, Jesus told his followers they would be cast out of the cultural centers of worship (the synagogue) and even killed by people who thought they were performing an act of service to God by killing them.

The result of the earliest Christians rigidness was twofold: many martyrs and many conversions. In the now famous words of Tertullian, “the blood of the martyrs is the seed of the Church”.14

Early Christianity was largely comprised of the lower classes, women, and especially slaves. Only later did members of the aristocracy join because it was “fashionable”, due to Emperor Theodosius I making Christianity the state religion at the end of the 4th century.

Some believe that Plotinus, the founder of Neoplatonism, “provided the philosophical framework in which many Christian thinkers expressed their theology and psychology”. This list includes such luminaries as “Gregory of Nyssa, Marius Victorinus, Augustine, Pseudo-Dionysius, and Boethius”. Neoplatonism can be defined as a philosophy “built on the teachings of Plato, this highly mystical challenge to Christianity taught that the goal of all humans was reabsorption into the divine essence. Reabsorption was accomplished through various processes including meditation, contemplation, and other mystical disciplines. Salvation was purely spiritual with no Jesus, no cross, and no atonement”.

See Robert M. Berchman in Encyclopedia of Early Christianity, ed. Everett Ferguson, Michael P. McHugh, and Frederick W. Norris (New York and London: Garland Publishing, 1990), 738. James P. Eckman, Exploring Church History (Wheaton, Il: Crossway, 2002), 22.

Ed. Geoffrey W. Bromiley, The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, Revised (Wm. B. Eerdmans, 1979–1988), 861.

See Augustine, Epistles 102 ad Deogratiam; Jerome, Comm. In Osee 1.2; Augustine, On the Harmony of the Gospels 1.10-1.11, and Marcarius Magnes, Apocriticus, respectively.

Cf. P.M. Casey, “Porphyry and the Origin of the Book of Daniel,” Journal of Theological Studies, n.s. 27 (1976): 15-33. For an example of a lay level yet apologetically sufficient refutation of the common critical scholar approach to the book of Daniel, see Josh McDowell, Daniel in the Critics’ Den: Historical Evidence for the Authenticity of the Book of the Daniel (San Bernardino, CA: Campus Crusade for Christ, 1979).

B. K. Waltke, “The Date of the Book of Daniel,” BSac 133 (1976): 319. See Young’s discussion, “Porphyry and His Criticism of Daniel,” in Prophecies of Daniel, 317–20.

Jerome’s Commentary on Daniel, trans. G. L. Archer, Jr. (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1958), 142.

Eusebius, Preparation of the Gospel 1.3.1 and Frag. 92.

This is if – as is probable – Minicius Felix’s Octavius 12 represents a comment by Porphyry, which some scholars think is the case.

Augustine, Epistles 102.8.

Augustine, City of God 19.23.

Robert L. Wilken, The Christians as the Romans Saw Them (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1984), 158.

Martin Hengel, Crucifixion: In the Ancient World and the Folly of the Message of the Cross, Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1977.

Apologeticus, Chapter 50.